10 common cyber attacks

Learn which types of cyber attacks are most likely to target your platform — and what you can do to prevent them.

Cybersecurity can often seem like a game of cat and mouse. No sooner do security experts get wise to the latest threats than attackers modify their tactics, discover fresh vulnerabilities, and develop new lines of offense.

Still, most cyber attacks fall into a known set of categories and follow a predictable pattern.

In this post, we review ten of the most frequently carried out cyber attacks, how they work, and what developers and users can do to protect their sensitive data.

What is a cyber attack?

A cyber attack is any attempt by malicious actors (often called cyber criminals or hackers) to breach a computer system, network, or database. A cyber attack can be launched against a single user or device or against a larger group — like a corporation or a governmental organization.

In recent years, there have been several instances of successful, high-profile cyber attacks against major global companies like Uber, Twilio, Okta, Microsoft, Samsung, and Cisco, to name just a few. And, alarmingly, some studies suggest that the overall number of cyber attacks is on the rise.

What's at risk in a cyber attack? What do hackers want?

Generally, hackers carrying out a cyber attack want to intercept, destroy, or otherwise tamper with online assets.

They may be out to steal sensitive data like account credentials, personal or financial information, or valuable intellectual property, or to install malicious software into a computer program to disrupt its operations. They may be doing this for monetary gain, for an ideological or political cause, or even just for fun.

All in all, it's a highly lucrative (and highly damaging) business, with each cyber attack carrying an average price tag of $4.35 million for the impacted company.

What are the most common types of cyber attacks?

There are ten popular types of cyber attacks that show up time and again in security circles. Below, we share what they entail, how to spot them, and which of the latest security methods can help keep them at bay.

1. MALWARE ATTACKS

Malware, short for malicious software, is an umbrella term for any invasive file, program, or malicious code introduced to a computer through a corrupt email attachment, malicious link, or fraudulent ad. In a malware attack, an unsuspecting user loads one of these programs when visiting a website, leading them to unknowingly install malware on their system.

There are many different types of cyber attacks that use malware, including:

- Viruses that attach themselves to legitimate files or programs a user employs, then replicate and spread across different platforms, software, and devices

- Ransomware attacks that encrypt data or files on a device and block a user's access until they pay a certain price (ransom) or meet a specified condition

- Spyware that secretly monitors a user's online activity, gathers data, and then relays it to a malicious third party

- Trojans that (like a Trojan horse) are disguised as harmless or desirable programs and trick a user into downloading a corrupt file

- Bots (short for robots) that are programmed to quickly and automatically carry out attacks, with the potential to infect and control many different computers at once

A classic example of a malware attack (in trojan form) is pop-up advertising for fake antivirus software. This corrupt "software" promises to rid a computer of viruses but actually introduces one to the system, as it gets a user to unwittingly install malware instead.

Recently, there's also been a growing trend of malware as a service (MaaS) products. In the MaaS market, cybercriminals can buy or lease pre-made software or hardware that they can use right away, increasing the efficiency and frequency with which they can carry out their malware attacks.

2. PHISHING ATTACKS

Phishing attacks are a form of social engineering. In a typical phishing attack, a hacker sends a message via email, SMS, social media, or another online channel, hoping to trick the recipient into disclosing restricted or sensitive data.

Phishing attempts are often carried out en masse and at random to ensnare the largest possible number of victims. But they can also be part of a more targeted campaign, in what's known as a spear phishing attack. Spear phishing attacks are tailored to a particular individual or organization to make the message and desired action seem more intimate and trustworthy. When this technique targets high-ranking executives, specifically, it's called a whale phishing attack.

One of the most well-known tropes used in phishing attacks involves an email scam where the author poses as foreign royalty, offering the recipient a share in a vast fortune if they help move the funds out of another country. As the story goes, the recipient must provide their bank account information, so the money can be transferred to them for safekeeping. Of course, an obliging reader will quickly find their account balance drained.

Many protective measures have emerged in recent years to prevent phishing attacks and spear phishing attacks, including unphishable multi-factor authentication (MFA) flows, which avoid commonly intercepted credentials like passwords and email or SMS one-time passcodes.

3. MAN IN THE MIDDLE (MITM) ATTACKS

In man-in-the-middle (MitM) attacks, a hacker eavesdrops on or otherwise gets hold of sensitive communications between a user/application and another platform. Think of it like a hidden, silent third party listening in on a confidential phone conversation.

MitM attacks can occur as either active or passive eavesdropping attacks:

Active eavesdropping attacks could take the form of session hijacking, where a hacker observes the web traffic occurring over a given network, locates an active session ID, and then uses the related session token to gain unauthorized access to a user's account.

In a passive eavesdropping attack, a hacker might create a free, public WiFi hotspot — like at a park or cafe — and get a full view of all the activities and data exchanges an unsuspecting user is participating in over that wireless network.

4. DENIAL OF SERVICE (DoS) ATTACKS AND DISTRIBUTED DENIAL OF SERVICE (DDoS) ATTACKS

A denial of service attack (DoS attack) occurs when a hacker floods a website or network with pointless or unnecessary requests — often from fraudulent accounts — overloading the system until it crashes or is shut down. This disruption means that legitimate users and user requests cannot access the site or service, thus thwarting its regular operations or business.

Think of a D0S attack like a prank caller continuously phoning a pizza shop during peak hours, tying up the line so real customers can't dial in with actual orders.

In a conventional DoS attack, this congestion is caused by a single source. In a distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack, however, it comes from many different sources at once.

In the pizza shop analogy, a DDoS attack would look like this: Imagine the prank caller has help from a dozen of his closest friends, each calling from a different phone. It would be next to impossible to trace and block each of these numbers to free up the pizza shop's line — which is why DDoS attacks can be more difficult to stop.

Given the bandwidth necessary to execute them, DDoS attacks are almost always carried out by programmed botnets, so taking bot-preventing measures like monitoring web traffic and rerouting or blocking malicious bot activity can help protect your system from a DDoS attack.

5. CROSS-SITE SCRIPTING (XSS) ATTACKS

Cross-site scripting attacks (XSS attacks) rely on code injections, where hackers insert malicious code — typically client-side, malicious JavaScript code — into a trusted app or website. In other words, an attacker targets a user by hiding harmful code behind seemingly harmless content, which they load into their browser.

Cross-site scripting attacks can occur when the data a user submits — like entering their name into a contact form — is not properly validated or escaped, allowing hackers to substitute the user's input with malicious JavaScript code that the browser executes automatically.

Alternatively, an XSS attack can take the form of shortened or disguised URLs in a phishing email — like a fake message from a user's bank that asks them to “click here” to resolve a problem — with the included link really just running a malicious script.

Following a successful XSS attack, a hacker can gain access to a user's credentials or hijack their account, control their browser remotely, or even spread worms and other malware across their entire system.

6. SQL INJECTION ATTACKS

Similar to an XSS attack, an SQL injection attack occurs when a hacker inserts structured query language (SQL) code into a standard request in order to breach or manipulate a vulnerable database.

One example of an SQL injection attack is when an app or website provides a form for users to enter their login information (like a username and password), which is then checked against the app's database to verify the user's credentials and grant them access. A hacker might use that form to insert SQL code instead — a programming language that allows them to communicate directly with the app's database and thus carry out their own requests.

The best way to prevent SQL injection attacks is to use input validation and parameterized queries, rather than inserting user inputs directly into SQL statements, but different cybersecurity experts will have different approaches to this issue.

7. DOMAIN NAME SYSTEM (DNS) SPOOFING

Domain name system (DNS) spoofing attacks are sometimes referred to by the names of their constituent parts — DNS cache poisoning and DNS tunneling attacks.

A hacker first impersonates a DNS server, which is responsible for translating the domain name a user enters (like google.com) into an IP address that a computer can understand and route to. Having intercepted a user's request, the hacker instead alters (or poisons) the information in the cache of the DNS server and reroutes (or tunnels) the user to their own fake IP address, which hosts a forged version of the desired website.

For example, a user may think they're heading to the Facebook login page — via facebook.com — but be redirected to a different domain hosting the hacker's fraudulent Facebook page. Any username and password the user enters there can, of course, be seen and stolen by the hacker and leveraged to breach the user's actual Facebook account.

8. BIRTHDAY ATTACKS

Birthday attacks are named after the birthday paradox in mathematics — which states that, for there to be a 50% chance someone at a party shares your birthday, you need 253 people at the event. But for a 50% chance that any two people there share a birthday, you only need 23 at the event, because you're not already tying one end of the pair to a specific date.

In cryptography, a birthday attack follows this same principle. It's much more challenging to find a collision or match with a specific hash function — a one-way algorithm responsible for encrypting, converting, and validating data like passwords — than it is with randomized attempts.

When successful, these more dispersed attacks can then be used to crack encrypted values like digital signatures.

9. DRIVE-BY ATTACKS

In a drive-by attack, the user doesn't actually have to download, open, or click on anything at all to install a hacker's program on their device.

Instead, drive-by malware can piggyback on a legitimate, authorized download and deliver a hidden, harmful payload along with it. In other cases, it can exploit security flaws on a legitimate website to transfer a malicious program onto a user's device.

Essentially, as the name implies, all a user has to do is visit or “drive by” a certain website to be affected.

10. PASSWORD ATTACKS

A password attack is really any attack that attempts to steal a user's password, and the term encompasses many of the above strategies. Still, there are a few unique terms and techniques that are used when hackers target traditional passwords specifically, including:

BRUTE FORCE ATTACKS

In a brute force attack, a hacker attempts to gain access to a secure account through trial and error, repeatedly entering random credentials like username and password pairs until one works.

CREDENTIAL STUFFING ATTACKS

In a credential stuffing attack, a hacker uses the correct credentials — which they've intercepted or stolen using one of the above attack vectors — to sign into a legitimate user's account and break into a secure system.

PASSWORD SPRAYING

Password spraying is a type of brute force password attack where hackers use the same common password across numerous user accounts before moving on and trying another, allowing them to bypass simple protections like login lockouts.

The good news is that it's relatively easy to prevent password attacks. It's as simple as not using traditional passwords in your sign up and log in flows — and instead relying on any of the secure, passwordless authentication options on the market to safeguard your app.

AND ON AND ON…

Unfortunately, this list is by no means comprehensive. Hackers are always adapting and refining their methods to bypass the newest security software, circumvent the latest cryptographic techniques, and come up with new cyber attack vectors that keep cybersecurity experts (and all internet users) on their toes.

That means there's a constantly growing arsenal of cyber threats, with others including zero-day exploits, internet of things (IoT) attacks, rootkits, and cryptojacking.

How to protect against cyber attacks

While we could write a whole post on the best ways to guard your business or personal data against cyber attacks — and, in fact, we did — there are a few simple measures you can take right off the bat:

Know your sources.

This may seem basic, but verify that each file you download is coming from a known and trustworthy source, avoiding exposure to malware.

Keep your software up to date.

You may be annoyed by pesky update reminders, or you may not have time to install the latest version of a program or app, but not following through can leave your device open to a cyber attack that the software company or operating system has already worked hard to solve.

Implement multi-factor authentication (MFA).

By taking a layered approach to authentication, requiring two or more credentials to verify a user's identity, multi-factor authentication (or MFA) is one of the best and simplest ways to secure your app or website against many different types of cyber attacks.

Better still, implement unphishable MFA, which uses end-to-end cryptography and key-based authentication to combat more sophisticated cyber attack methods like SIM swapping, which can compromise secure SMS-based one-time passcodes.

Get rid of traditional passwords.

As a company specializing in passwordless solutions, we'd be remiss if we didn't remind you that traditional passwords are the weakest link in the authentication game — whether they're easily forgotten, repeated across multiple accounts, or just downright easy to guess — and removing them from your auth equation is the only foolproof way to prevent a costly password attack.

Remember: The vast majority of data breaches (81% or more) can be traced to compromised credentials, which is why industry experts at the Open Worldwide Application Security Project (OWASP) advise that all traditional passwords should now be considered "pre-breached."

It's just not worth putting your data at risk when there are plenty of secure, alternative auth solutions at your fingertips. And if you must use passwords, use a next-level, modern version that eliminates conventional UX flaws and vulnerabilities.

What Stytch is doing to prevent cyber attacks

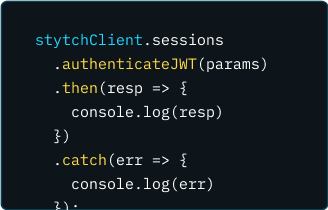

In the fight against cyber attacks, we're equipping developers with the latest, strongest passwordless products, from email magic links to SMS one-time passcodes to WebAuthn built-in biometrics and specialized hardware keys.

To get started, sign up for a free account, and try our solutions out in a sandbox environment to see what they can do for you.

Build auth with Stytch